Saraighat, situated in the western extension of the Ahom kingdom, emerged as a place of importance in the seventeenth century. During that time, the political map of Assam was under a constant state of fluctuation due to the repeated invasions of the Mughals. Saraighat was separated from Gargaon, the Ahom capital, by a distance of nearly 320 kilometres.

The present Saraighat, a part of greater Guwahati, is accessible. through various modes of transport – road, rail, air and water. But this place of pride which witnessed and recorded a series of triumphs and defeats of the Ahoms against the Mughals now appears to be a place proceeding to an unworthy future.

Prior to the occupation of the Ahoms, Srighat or Saraighat was under the control of the Koch kingdom. The contemporary Muhammedan expeditions gradually opened a way for the Ahom king Pratap Singha (1603-41) to expand the western’ boundary of his dominion under the pretension of assisting the weak Koch ruler.

Pratap Singha eventually occupied Pandu and fortified it. The post of Barpukhan was thus created to govern the newly acquired tract west of Koliabor. Langi Panisiya, who distinguished himself in the battles against the Muslims, was made the first Barphukan. The post of Barbarua was also introduced at the same time to administer the region east of Koliabor outside the jurisdiction of the central ministers of the Ahom monarchy. Momai Tamuli was the first Barbarua.

Guwahati at that time “wholly or chiefly” was on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Historical documents of contemporary period support the existence of three Ahom forts in this region. – at Pandu, Agiathuti and Saraighat respectively. They were constructed at the instance of Pratap Singha against the Mughal invaders. All these forts were demolished by the Muslims more than once during his reign. The fort of Saraighat constructed without the aid of bricks or iron tools was protected by a fence of pointed stakes set firmly in the ground. It suffered another demolition when Mirjumla, the governor of Bengal, invaded this country in the early part of 1662. Guwahati was made the Mughal! headquarters from that time onwards.

The fall of Srighat into the hands of the imperial power gave it a national importance. Mirjumla proceeded towards the Ahom capital. According to Gait, the historian, the resistance of the Ahom army was so feeble that Sihabuddin, the writer who accompanied Mirjumla, did not even mention it in his account.

Jayadhwaj Singha, the helpless Ahom king, appealed for peace; but the invader refused, suspecting the proposal to be a pretext to cause “delay or decrease in the vigilance” of the Muslims.

The strategic environment brought the Ahom envoys to Mirjumla’s camp several times with presents and unceasing appeals for peace. The Mughal general replied that he would soon be at Gargaon and would personally discuss the matter with the king.

Frightened, Jayadhwaj, who had already become a fugitive, continued his flight till he reached Namrup. A number of nobles and about five thousand men followed him. However, the people reacted to the flight of ‘their king in a different way. It diminished their spirit and with widespread hatred, they regretted their, loyalty to the “bhagania raja”. Mass depopulation started and out of their political and economic insecurity, some of them did not even hesitate to join the pro-Mirjumla camp.

The royal palace of Gargaon soon, fell into the hands of the enemy. Betrayal of the Ahom royalty made the inhabitants accept their subordination to the new authority. But such a situation appeared to be temporary as soon as the rainy season started. Heavy floods made locomotion difficult and Mirjumla suffered a cut-off at the waterlogged Gargaon. The distress caused by the lack of communication and supply was furthered when epidemic disease attacked the camp. It reduced their manpower from fifteen hundred to five hundred; the horses and cattle were also not spared.

The Ahom king, at last, found a shore and quickly fell on the devastated enemy. Mirjumla had no other way but to wait patiently for the end of the rainy days. The land slowly dried up and with the opening of land communication, reinforcements arrived in his camp. Their fresh operations again made the king fly away.

Baduli Barphukan, who was the commander-in-chief of the Ahom army in western Assam against the Mughals, crossed over to the Muslims after Mirjumla occupied his entrenchments

The next phase took a different turn. Baduli Barphukan, who was appointed the commander-in-chief of the Ahom army in western Assam against the Mughals, was now in charge of defence of the north-eastern side of Gargaon. Mirjumla occupied his entrenchments and the Barphukan crossed over to the Muslims; he was followed by many others. Baduli even submitted to Mirjum a plan for searching out the Ahom king. Thus the people “unique in the world in deception, lying and breach of faith” brought Mirjumla to a comparatively better position. The Barphukan thousand fighting men for this purpose and rewarded with the subedarship of the country between Gargaon and Namrup.

But before any more notorious examples of moral breach could take place, the Mughals again fell short of supplies due to a severe famine in Bengal. Mirjumla himself fell seriously ill and his troops showed their total reluctance to spend another rainy season in Gargaon. He was compelled to make peace.

The treaty of Ghilajharighat (in Tipam) was concluded accordingly in January, 1663. Treaty provisions claimed Ramani Gabhoru, the only child of Jayadhwaj Singha for the Mughal harem. Barnadi in the east of Saraighat and Asurar Ali on: the southern bank of the Brahmaputra were made the boundary lines between the Ahom and Mughal territories. Assam became a tributary kingdom of the imperial power and Guwahati was made the headquarters of the Mughal administration. Ramani Gabhoru was later on (in 1668) married to Azamtara, the son of Aurangzeb.

Jayadhwaj Singha never faced the strength of the Mughals, but tried to attack them only when natural calamities landed them in unfavourable conditions. Though it was not unnatural for the Ahom army on foot to fear the speedy enemy on horseback due to the rareness of the animal in Assam, the actual difficulty was in the fact that the local army with swords, spears, bows and arrows could not hope to win against an army with cannons.

The relations between Assam and the imperial dominion were not a natural type of kinship; they were a part of a penalty treaty. Chakradhwaj Singha (1663-69), the next king, in his initial attempt to restore the lost prestige, refused the Mughal claim of the yearly indemnity and elephants on the plea that there was no money in the treasury and the elephants were not properly trained.

The breach on the question of payment of tribute could not be mended. The Ahom king in his preparation for another encounter, remained busy in repairing the forts and bringing perfection to his army.

Lachit, the son of Momai Tamuli Barbarua, was selected for the generalship of the Ahom army and he was appointed the Barphukan.

Lachit, the son of Momai Tamuli Barbarua, was selected for the generalship of the Ahom army and he was appointed the Barphukan. The previous Muslim invaders had already caused an influx of fire-arms to Assam. The fresh campaigns were decided to be carried on with some improvements in war technique in addition to the use of these arms and the horses and elephants snatched from the invaders. By the time of the Battle of Saraighet (1671) the Ahoms were able to make their own cannons.

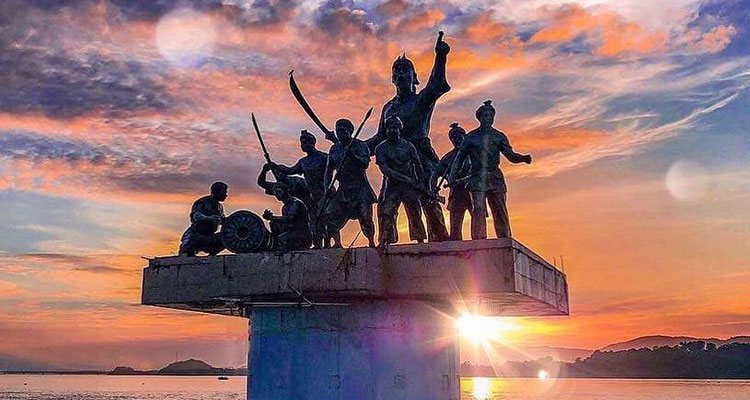

Lachit recovered Guwahati from the Mughals and made it the headquarters of the Barphukan. He fortified Pandu and Saraighat strongly. The imperial reply to this arrogance was the despatch of a huge army under the generalship of Ram Singha. On getting the news, Lachit made haste to complete all preparations before they reached Guwahati.

The furious Lachit at once beheaded him, roaring that his maternal uncle was not greater than his country.

In spite of it, during his midnight inspection, the Ahom general found that the labourers, who were supposed to complete a fort at Saraighat overnight, were deep in slumber. His maternal uncle who was given the charge of construction confessed that. the people were very tired after the strenuous day of labour and had taken rest. This was not accepted by Lachit as atonement for the crime his uncle had committed by negligence of duty. The official failure to display mass patriotism through the labour force resulted in a fatal penalty for the uncle. The furious Lachit at once beheaded him, roaring that his maternal uncle was not greater than his country. The “ferocious manner and brutal temper” brought the startled labourers into alertness, and the Momaikatagarh was completed before dawn. History does not give any hints if the time factor was overcome by increasing the numerical strength of the labour force.

Saraighat thus witnessed a pre-battle reaction on the point of contrast between the rigidity of a general and the leniency of an official. The sympathy of the one towards the exhausted labourers failed to subside the anger and anarchic liberty of the other which coincided with his professional obligations.

The regime of Chakradhwaj Singha recorded another haughty utterance of Lachit Barphukan when Ram Singha sent an envoy to the Ahom camp demanding the boundary line under the old treaty. Lachit answered back that he would rather fight than evacuate an inch of the territory.

However even after this “bombastic announcement” Lachit failed to establish his superiority; he retreated and faced the enemy in two battles near Tezpur. The situation was soon overcome and the Mughal fort at Agiathuti was captured by the Ahoms. The next encounter again brought defeat to Lachit and he was severely condemned by the king, Udayaditya Singha who succeeded Chakradhwaj in 1670.

The static demand of the Mughals to maintain the old boundary line and recurring warnings for it slowly tended to cause a breakdown in the Ahom spirit. While the Buranjis are frank enough to express that Lachit too showed his intention to hand Guwahati over to the enemy, they are silent about the reason. Possibly Lachit felt that the distant frontier otherwise would never be peaceful even at the cost of a serious damage to the Ahom army. Udayaditya did not give his consent to this plan and as a result, Saraighat again captured the attention of the two rival forces. The place was soon awakened with a fight against the enemy till the Mughals were chased beyond the Manah river.

The defeat in Saraighat was not the final destruction of the Mughal power; it accepted by the vanquished as a temporary failure. Still, there was a lull between the two parties for a period of about eight years. This period is important from some other dimensions as well. To start with, a survey of the historical events will make us aware of the fact that the mother and wife of Ram Singha asked him not to lead the expedition to Assam if he did not desire an untimely death. They stressed on the point that if a person so brave as Mirjumla perished by invading this dreadful land of magic, what hope was there for Ram Singha? But this superstition was subjected to dilution when instead of Ram Singha, the Ahom general himself met a tragic death after a few days of the battle. Both Mirjumla and Lachit were weakened by the illness which they caught during their respective confrontations. Mirjumla died of pleurisy before he reached Dhaka. Lachit succumbed to his high fever after a life span of fifty-nine years (1612-1671).

The battle of Saraighat continued for four months. But the factual contradictions between the Buranjis on its operations lead us to believe that they were not recorded from the day-to-day events. Probably, owing to the chaotic condition of the country, they were written at a much later time, and that too from half-buried memories. It is therefore quite natural that the sad demise of Lachit, who guided the fortune of the country, made way for the emotional people to start a hero-worship by excessive admiration of the great general.

The so-called “heroic age”, was followed by a period of anarchy.

The so-called “heroic age”, instead of giving birth to a race of men heroic, was followed by a period of anarchy. The long absence of the Ahom officials of high rank from. the capital city during the Ahom-Mughal conflict liberated the evil forces that were so far controlled by the autocratic king. It encouraged militarism and a fratricidal conflict started among the nobility to capture power. Udayaditya was poisoned to death and his four consecutive successors also fell into the hands of assassins.

The Buragohain (Atan Buragohain) and the Barphukan (Laluksola) also involved themselves in some conspiratorial plans to overthrow each-other on the question of legitimacy of their respective powers and authority. Laluksola, who succeeded Lachit as the Barphukan, soon was proved to be a morally unfit person for the post.

Laluksola entered into a series of treasonable communication with the Nawab of Bengal. He even promised to cede Guwahati to the Mughals in exchange for help to retain power. Prince Azam came accordingly with a huge army and the Barphukan surrendered Guwahati to him in March, 1679. It seems that the interpretation that there was secret interference and guidance by Ramani Gabhoru in this plan was not without any ground.

The fratricidal warfare ended with the accession of Gadadhar Singha in 1681. He recovered Guwahati from the Mughals the next year. However, this time the base of operation was shifted from Saraighat to Itakhuli, on the opposite bank.

The battle of ltakhuli was the last Ahom-Mughal conflict.

The door of the country was opened to the authority of Bengal for a second time in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The entry was welcomed as British bayonets were essential to expel the Burmese invaders from the Brahmaputra valley. After their occupation of Assam, the British removed the communicational discomfort caused by the vastness of the Brahmaputra by abandoning the northern bank as a centre of administrative dealing. Though the waterway was maintained for commercial transactions, the administrative linking up of Assam with Bengal was done through Sylhet. The new rulers selected Cherrapunji as the capital for its proximity to the Bengal frontier and south Guwahati was connected with it by roadways; the capital was shifted to Shillong afterwards.

The isolation of Saraighat from successive political perils hardly diminished its inspirational value on the Assamese mind. Yet, it is playing a mythical role keeping the realities at a distance. The people are reluctant to withdraw the myth. The reason behind it may be that it is not recent but generated in the popular mind more than three hundred years ago. It appears that instead of passing this mythical conception to the succeeding generation, an impartial look into the matter should be taken in a historical light and the reality should be found out. The place still possesses some visible signs to depict that once upon a time the Assamese had proved to the Mughals that they were the masters of this country. This will be a true tribute to Saraighat.

This article was first published in The Sunday Sentinel on 02 May 1993.